A parade of SUVs, a carnival of marigold garlands, conversations that ascribe numbingly high virtues to small elections and douse contenders in a feeling of pride so weighty that the spectre of it precedes the very purpose of it. Even if we keep the euphoria of electoral glories and the grand tragedies of electoral losses aside, nation building in itself is a pretty cool thing. What could be cooler than taking a specialisation one has earned through an academic degree along with field exposure, to the insides of a government’s workings and converting knowledge into action and change. Imagine the power to be able to oust pollution from outside your child’s window, the power to be able to improve the life of the farmer who is growing your next meal, the power to be able to infuse concepts like ‘evidence-based interventions’ and ‘outcome budgets’ into government systems that have historically done things differently.

Typically, at least in India, there have been three broad ways to practice #nationbuilding, the primary one being politics. This field requires money, an affiliation to a cadre or an ideology and it does not guarantee a stable income. An electoral outcome might or might not correspond to a candidate’s performance in public delivery.

The second way is bureaucracy, which is a more structured way of lending one’s life to governance and impact. Today, the steel framework of the services is rusted and in need of revitalising. Be it demonetisation, GST or Aadhaar, the success of implementation of any national decision rests entirely on the competence of the bureaucracy. To be able to implement such colossal policies that require intricate implementation, a machinery of human resources that is empowered by technology and specialised training is required. Moreover, bureaucrats are subjected to a range of institutional checks by MPs, MLA, the Central Vigilance Commission and through the Right to Information Act. If a senior officer signs on a document under pressure, an inquiry can be initiated. The institutional checks, the political pressure and the mammoth duty to execute big schemes is bound to leave those who are fitted into these colonial systems, even more exhausted. Till date, the bureaucracy is held accountable individually and not institutionally. The combined effect of these factors is risk aversion by bureaucrats that tilts them towards adhering to the purity of procedures and quite away from logical reasoning.

The third and the most flexible way to dive into Nation Building is in the social impact space, which features both social impact investing and social impact consulting. The floodgates of the sector, which is a bridge between private funds and international grants and the systems doing public delivery, have now opened. A whole new generation’s energy and imagination is ready to be pumped into thirsty public systems. This new space differs in character and quality from well-meaning NGOs that worked in silos, or on the peripheries, mostly exhausting themselves in advocacy and celebrating small wins that came after decades were lost, and from those activists who revelled in the romance of resistance and refused to turn their angst into collective action to remedy social injustice, and from those student leaders who stuck the same posters and recited the same slogans without a degree of agency, or imagination.

The new social impact space is action-oriented and evidence-based. It harnesses the forces of social entrepreneurship, of innovation and private capital, to battle today’s greatest challenges.

Investing in climate, in equal wages, in equality and progress of classroom learning, in technology that aids any of the above, is a good strategy. Aside from the moral satisfaction, the space offers a better balance of risk and reward and is far less volatile. Today, you can make money even while solving a problem and that is the key to making this sector sustainable and attractive to the best talent out there.

‘Lateral entry’ or the entry of experts into a system isn’t a new thing. Dr Manmohan Singh, neither a bureaucrat nor a politician, was appointed as chief economic advisor in 1972 and later hired as a secretary in the finance ministry in 1976. From Montek Singh to Vijay Kelkar to Bimal Jalan, the country has put matters of finance in the hands of experts. Long before that, a man named VP Menon worked in the shadows of Sardar Patel, to stitch together a nation that was then unborn. He did not belong to the services but his political acumen, his brazen charm of speaking truth to power, had put him at the frontline of India’s constitutional progress since 1918. Menon was the principal typist of the first draft of the Montagu-Chelmsford Report. Carving a role for himself at the Reforms Branch, he helped implement the Government of India Act, 1935. Fully familiar with the dynamics of the princely states, he drafted the Instrument of Accession.

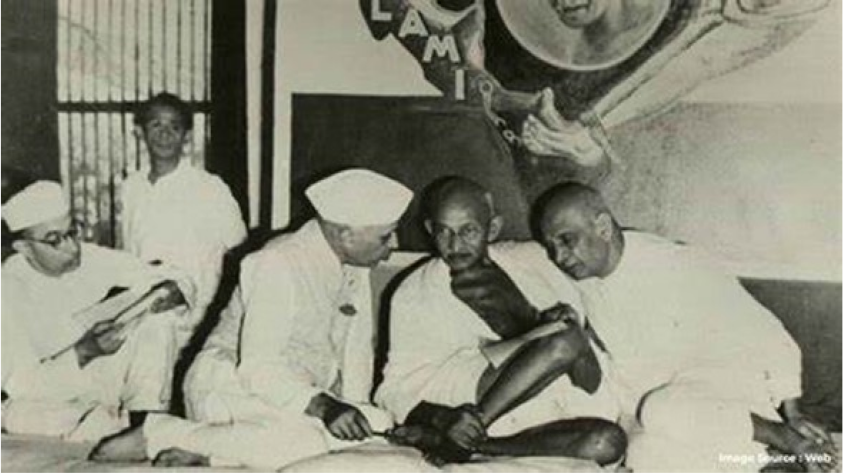

The Mahatma’s softness towards the princes, considering them trustees of their people, Nehru’s antimonarchical views that lacked strategy, he walked behind Sardar’s shadows and foiled Mountbatten’s plan of offering each princely state a choice to declare itself independent. He came out of no set structure and turned around a plan with tact, research, action.

Nation building is as cool today as it was back then.