Every year, as winter descends upon northern India, a suffocating haze engulfs the region, turning the skies gray and toxic. This seasonal air quality crisis, particularly acute in urban centers like Delhi-NCR, becomes a public health emergency. The primary culprit, as goes the common narrative, is stubble burning—a practice where farmers set fire to agricultural residue left after harvest. Different researchers have attributed different percentages to the contribution of stubble burning to Delhi’s air pollution; however there is widespread acceptance that the contribution is significant enough to bring in holistic and sustainable solutions to the menace.

While stubble burning may appear to be a simple agricultural technique to manage the agricultural residue, it has evolved into one of the country's most pressing environmental concerns. The numbers are staggering: tons of crop residue go up in flames annually, releasing dangerous pollutants that choke cities and impact public health. Despite the severe consequences and growing public outcry, this practice continues. Many wonder why farmers resort to such a harmful method and what makes this issue so complex.

Understanding stubble burning by exploring its roots in agricultural traditions and the economic pressures driving it is key to addressing the challenges and finding a sustainable solution.

What is stubble burning?

Stubble burning refers to the act of setting fire to crop residue remaining after harvesting. This agricultural residue, known as stubble, consists of the lower parts of plants left behind after the valuable portions have been collected. The practice is prevalent in the months of October and November across Northwest India, especially in the states of Punjab, Haryana, and some districts of Uttar Pradesh.

In Punjab, paddy is cultivated on approximately 31 lakh hectares, producing around 20 million metric tons (MMT) of straw, while Haryana cultivates about 14 lakh hectares of paddy, yielding roughly 9 MMT of straw. Due to these staggering figures, stubble burning is often associated with paddy straw.

Why is it important to reduce stubble burning?

Stubble burning releases large amounts of toxic pollutants, including particulate matter (PM), carbon monoxide (CO), volatile organic compounds (VOCs), and carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, which disperse and transform in the atmosphere, and form a thick smog that harms human health. When PM particles are inhaled, they enter the bloodstream, leading to permanent health issues. Burning paddy straw also leads to a loss of soil fertility by depleting vital nutrients such as nitrogen, sulfur, potash, phosphorus, and other micronutrients. The heat generated from burning crops penetrates the soil resulting in a loss of moisture and organic content. These nutrients must be replenished for the next crop cycle by adding fertilizers to the soil, which increases farmers' fertilizer expenses. Additionally, stubble burning represents a lost opportunity, as the stubble could be repurposed into pellets and bales for industrial fuel, animal fodder, and other uses. Despite its environmental hazards and economic costs, many farmers continue to opt for stubble burning.

Why do farmers resort to stubble burning?

Stubble burning results from a combination of factors, including a shorter crop sowing window, the cost associated with managing stubble, high mechanization, and lower market demand for ex-situ stubble usage. Let's explore these reasons in detail:

- Delayed Paddy Sowing Leading to Shorter Window between Harvesting of Paddy and Sowing of Next Crop: In 2009, Punjab and Haryana enacted laws to conserve groundwater. The law prohibits farmers from sowing paddy before May 10 and transplanting it before June 10, thus delaying rice transplantation to align with the monsoon season. This shift pushed the harvest to late October and early November, reducing the time available for wheat sowing and exacerbating stubble burning.

- Long-Duration Paddy Varieties: The PUSA-44 variety of paddy, which generates good yield and thus has been promoted actively by all stakeholders, takes 150–160 days to harvest, further narrowing the window between harvesting of paddy and sowing of next crop and encouraging burning as a quick solution.

- High Costs of Management: Managing stubble in the field through either Crop Residue Management (CRM) machinery or through ex-situ mechanisms costs between ₹1,500 and ₹2,500 per acre, which many farmers cannot afford.

- Mechanization and Labor Costs: Combine harvesters, widely used in Punjab and Haryana, leave stubble behind. High labor costs make manual harvesting unviable, pushing farmers toward burning.

- Nascent Ex-Situ Management Systems: The aggregation and supply chain for alternative stubble uses are underdeveloped, requiring substantial investment to scale. Current uptake of stubble for industrial use remains limited.

A Complex Solution: More Than Meets the Eye

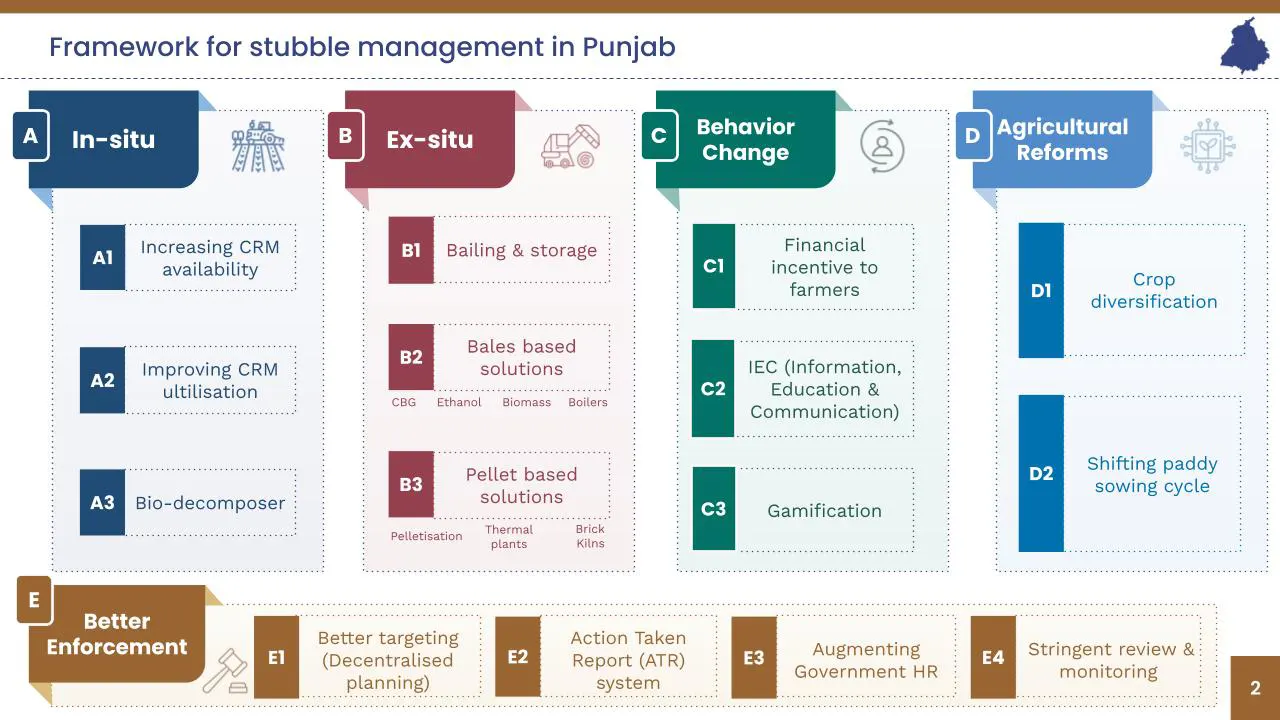

Despite the plethora of challenges, innovative approaches can help farmers manage stubble more sustainably. Here are key solutions and interventions needed to scale them up:

-

In-Situ Management of Stubble: The government

operates a CRM scheme to subsidize the cost of Crop Residue

Management (CRM) machines. However, the primary challenge lies

in managing the operational expenses associated with these

machines. To address this, the government should provide direct

cash incentives to farmers for on-site operation of CRM

machines. In-situ stubble management offers significant

environmental benefits and is relatively easy to scale.

Providing cash incentives, coupled with a robust review and

monitoring mechanism, could substantially enhance the

utilization of stubble management practices.

Nonetheless, the distribution of these benefits and the allocation of funds between central and state governments demand thorough policy deliberation. Effective implementation also requires close collaboration between these government bodies to ensure the success of the initiative. -

Ex-Situ Management of Stubble: Ex-situ

solutions, such as producing compressed biogas (CBG), utilizing

stubble in industrial boilers, thermal power plants, biomass

power generation, and pelletization, present promising

market-based alternatives. However, these options face several

challenges, including inefficiencies in aggregation and supply

chains, high capital investment requirements, low market demand,

and industry reluctance due to uncertainties. Additional hurdles

include delays in regulatory clearances and extended gestation

periods for investments.

Addressing these barriers requires sector-specific policy interventions. These policies should include fiscal support, viability gap funding, and mandatory market creation for stubble-based industries. Such measures would be instrumental in increasing the uptake of stubble in industrial applications and ensuring the viability of these solutions. -

Crop Diversification: Historically, farmers

have been encouraged to grow paddy and wheat to ensure national

food security. Similarly, they can now be guided towards

diversifying into crops like maize, millets, cereals, pulses,

and oilseeds. These crops require less water and are easier to

manage in terms of agricultural residue. However, for such a

transition to be feasible, it would necessitate the introduction

of Minimum Support Prices (MSP) for these alternative crops,

along with guaranteed market procurement at supported prices.

While crop diversification is a long-term measure, it is essential for transitioning farmers away from paddy cultivation. This shift would not only address the issue of stubble burning but also contribute to sustainable agricultural practices in the long run. - Incentives to farmers, leading to behavior change: While ex-situ initiatives and crop diversification will require systemic changes and time to yield results, immediate impact can be achieved by providing cash incentives to farmers for managing in-situ stubble. If the Governments of India and Punjab offer cash incentives to cover operational costs, we can expect a substantial reduction in stubble burning. Addressing farmers' genuine needs with such incentives will also empower the government with the moral authority to enforce the law.

The Way Ahead

Effective stubble management is crucial for sustainable agriculture and environmental health. Achieving this goal requires close collaboration between central and state governments, fiscal support, and efficient allocation of funds to promote alternative practices. Robust Information, Education, and Communication (IEC) campaigns can raise awareness among farmers about the benefits of these methods and how to implement them effectively. By combining policy interventions, financial incentives, and educational initiatives, India can significantly reduce stubble burning and promote sustainable agricultural practices and contribute to better air quality.