Stubble burning is a familiar headline across newspapers every winter, as temperatures dip and slow-moving winds trap pollutants, creating severe air quality dips across northern India. This perennial seasonal crisis continues to spark debates and concerns, yet sustainable solutions remain elusive.

As explained in a previous blog, the issue of stubble burning is particularly acute in northern Indian states where paddy (rice) is extensively cultivated, such as Punjab, Haryana, western Uttar Pradesh, and the National Capital Region (NCR), with Punjab being the largest contributor. Once the paddy crop is harvested, the residue in the form of paddy stubble needs to be cleared from the fields before the seeds of the next crop are sown. The clearing of fields without burning the paddy stubble is termed as stubble management.

Stubble management falls into two broad categories: ex-situ (outside the field) and in-situ (within the field). Ex-situ management involves cutting or uprooting the stubble and utilising it primarily for producing Compressed Biogas (CBG) or biomass power, using it as fuel for industrial boilers, co-firing it as pellets in thermal power plants, or even repurposing as cattle fodder. In-situ methods, on the other hand, involve managing the stubble within the field itself, by mixing the paddy stubble left after harvesting directly into the soil, hence enriching it. Both methods - ex-situ and in-situ - require specialised machinery, known as Crop Residue Management (CRM) machines. These machines often need to be attached to a tractor, making stubble management cost-intensive and time-consuming. For a farmer who only requires CRM machinery once a year during paddy harvest, purchasing one is a steep investment with limited upfront returns. Moreover, using CRM machines involves recurring operational costs, such as fuel for tractors and maintenance, adding to the financial burden. For a farmer with 5 acres of land, not only will they have to spend ₹1 Lakh to purchase a CRM machine on subsidy, but also bear operational expenses of ₹700-800/acre. Unsurprisingly, small and marginal farmers, particularly those without easy access to tractors, shy away from this expense. Adding to these financial challenges are prevalent misconceptions about CRM machinery. Some farmers believe that incorporating straw into the soil attracts rodents and increases the risk of pink stem borer (sundi) infestations. Others feel that mulch-covered fields appear "unclean" and worry this might reduce wheat yields. Consequently, many farmers continue to burn crop residue, which is a quick and cost-free method to clear fields for the next cropping cycle. However, this practice incurs a hidden cost. Burning stubble over in-situ stubble management depletes the soil of vital nutrients. Anything produced from the soil should go back into the soil to retain its fertility. Otherwise, soil fertility reduces over time which forces farmers to depend more heavily on synthetic fertilisers, increasing input costs while further degrading soil health.

To support farmers in environment-friendly paddy straw management and easier access to CRM machinery (both from capital and operational cost perspectives), the Government of India (GoI) and Government of Punjab have designed some initiatives. For capital cost support, GoI has been subsidising CRM machines since 2018 under the centrally-sponsored Crop Residue Management scheme. Individual farmers receive financial assistance covering up to 50 percent of the machine cost, while Custom Hiring Centres (CHCs), such as Primary Agricultural Cooperative Societies (PACS), Registered Farmers Groups (RFGs) and panchayats, receive up to 80% subsidies. The idea is that farmers who cannot afford to buy CRM machines can rent them from CHCs. Since 2018, over ₹2,000 crores have been allocated to facilitate the purchase of over 1.45 lakh CRM machines in Punjab alone, intending to promote stubble management practices across the state’s 31 lakh hectares of paddy fields. For operational cost support for small and marginal farmers, the Government of Punjab has issued guidelines for the CHCs to provide the CRM machines to farmers for no or marginal rental.

Theoretically, these efforts should have eliminated, or in the least, substantially reduced stubble burning in Punjab. A single primary CRM machine like a super seeder (which can independently manage stubble on a harvested field) can ideally handle stubble in at least 30 hectares per season. With over 75,000 primary CRM machines—such as super seeders, happy seeders, and surface seeders— deployed across the state, 75% of the entire paddy acreage of Punjab (22.5 L ha out of the total 31 L ha) could be covered. Yet, stubble burning persists at alarming levels. So where is the gap?

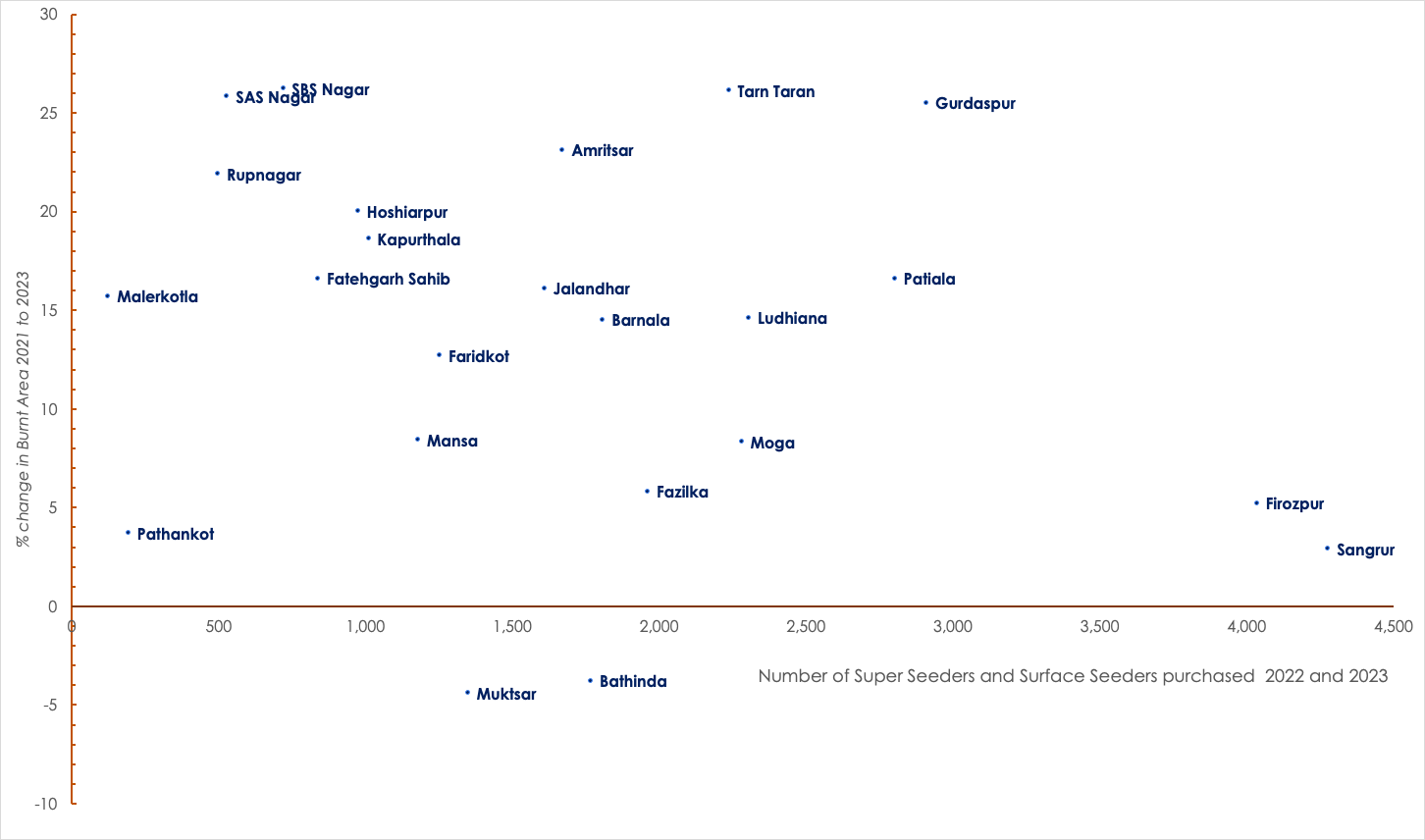

The problem lies in utilisation. Despite the widespread distribution of CRM machines, their use remains suboptimal. If utilisation was optimal, increased availability of CRM machines would have directly translated into reduction in burning. However, data shows a weak correlation between the number of CRM machines distributed between 2021 and 2023 and the reduction in burnt areas during the same period. Even districts with high machine availability have not demonstrated significant decreases in stubble burning.

As evident in the graph above, only Muktsar and Bathinda districts in Punjab experienced a decrease in burnt area following distribution of CRM machines, while the remaining 21 districts of Punjab showed no such improvement. For instance, Sangrur, which received the highest number of CRM machines in 2022 and 2023, saw an increase in burnt area.

This analysis reveals that while over ₹2,000 crore has been invested in the distribution of CRM machines since 2018, it is not necessarily effective. The government's focus has primarily been on distributing CRM machines, but it is imperative to rethink the strategy and prioritise increasing their utilisation to achieve meaningful results. Since the inception of the CRM scheme, approximately 12,000 CRM machines (10% of the total distributed) have been allocated to PACSs, while around 40,000 machines (25%) have been distributed to Registered Farmer Groups (RFGs).

However, the utilisation of machines owned by PACSs has remained suboptimal, as farmers are generally reluctant to rent these machines due to their poor condition and a lack of intent to manage straw effectively. Similarly, the utilisation of CRM machines by RFGs is constrained because members typically do not share their machines with other farmers. While some RFGs do not share machines because they are fully utilised by group members during the harvesting period, leaving little scope for lending them out, others avoid sharing to maintain exclusive use of the group's machines, fearing potential mishandling or damage by others.

In 2022, recognising the need to review the utilisation of CRM machines owned by PACSs, the Department of Cooperation implemented an online portal to track hourly utilisation data, which was to be logged by the PACSs themselves. In 2023, we initiated regular reviews with Deputy and Joint Registrars of Punjab to monitor CRM machinery utilisation via portal data and oversee new machine procurement. However, the initiative fell short of expectations due to low portal usage by PACSs and the submission of inaccurate data.

Despite these monitoring efforts, additional measures which actually address the condition of CRM machines owned by PACSs and incentivise improved rental operations are essential for significantly enhancing their effective deployment and usage. This requires a more comprehensive strategy, which should include the following measures:

- Encouraging private CRM machinery rental models. These private entities owning CRM machines and operating as CHCs will likely maintain their machines in optimal condition and also motivate farmers to rent them to sustain their business operations, which government-run CHCs haven’t been able to do very successfully, often due to lack of funds for maintenance and workforce constraints. In 2023, the government introduced ‘rural entrepreneurs’ as a new CHC beneficiary category under the CRM scheme to promote such initiatives. However, the lack of a clear definition of who qualifies as a rural entrepreneur has hindered the effective implementation of this promising step.

- Making better use of the allocated IEC (Information, Education, and Communication) funds to run targeted campaigns addressing common misconceptions farmers hold about stubble management. Such campaigns could emphasise the long-term fertility benefits and financial gains of adopting in-situ methods.

- Earmarking some funds within the CRM scheme for repairing machines owned by CHCs to ensure their continued functionality.

- 4. To improve rental efficiency, the rental business for Custom Hiring Centres (CHCs) can be incentivised and gamified. For instance, funds allocated under the Department of Agriculture and Farmer Welfare’s IEC Plan for incentivisation and felicitation of high-performing FPOs and PACSs could be utilised to reward PACSs demonstrating strong performance in CRM machinery rentals. This could be measured through metrics such as achieving a minimum average rental of 80 hours for relevant CRM machines

These are critical steps the government must explore to enhance the efficacy of its stubble management initiatives and support sustainable farming practices. Simply focusing on the distribution of CRM machines will not resolve the long-standing issue that has plagued Punjab for years. Unless the emphasis shifts toward maximising the utilisation of the machines already distributed, this recurring problem will persist year after year. Addressing the root causes of the stubble crisis and ensuring effective implementation is essential to breaking this cycle.