On June 16, the Government of India released a Gazette notification that has long been anticipated. The 16th decennial Census, set to begin with house-listing operations on June 16, has formally been launched, marking a historic restart to one of the largest administrative exercises anywhere in the world.

Conducted every ten years since 1871, the Census of India has long been the backbone of national planning. It informs decisions that affect everyone from delimitation of constituencies and reservation quotas to the allocation of government funds for welfare, education, infrastructure and beyond. Delayed by over four years due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the upcoming census — now scheduled to begin in phases from October 2026 — represents far more than a routine decennial effort carries more than statistical weight—it represents an important opportunity to reconnect India's policies with its people, backed by up-to-date and accurate demographic data.

It is a bedrock of evidence-based governance. The data it yields informs everything from school construction in remote villages to digital payment networks in crowded cities. And with a six-year gap since the last enumeration, the stakes in 2027 are particularly high. India has changed dramatically since 2011—in migration, employment patterns, urbanization, family size, fertility rate, and public health—yet we’ve been making policy decisions in the absence of a current, unified demographic picture. The census will help restore that clarity—and recalibrate how the state engages with its citizens

The upcoming census is expected to deliver not just fresh data, but a reimagined way of collecting it. For the first time, India will conduct a digital-first enumeration, marking a departure from the traditional paper-based methodology that has characterized India's demographic data collection for decades. This app will include features like georeferencing, real-time syncing, and skip logic, making it possible to conduct large-scale surveys with higher precision and efficiency, even in areas with challenging geography or patchy connectivity.

The idea of a digital census is powerful. It promises to address delays, data accuracy, resource optimization and accountability—four long-standing challenges of previous censuses. No longer will we wait years for tabulated results. With technology-enabled enumeration, validation, data entry, processing and analysis can happen in real time. Questions of digital literacy, internet connectivity in remote areas, data security, and the capacity to train 30 lakhs enumerators in digital tools loom large.

In this context, the recently completed digital baseline survey in Jammu & Kashmir offers more than just encouragement—it provides a tangible, field-tested blueprint for what large-scale, technology-enabled enumeration can look like in India today. Precisely because of the challenges it confronted—digital readiness, enumerator training, public trust, and logistical complexity—it stands out as a timely and essential case study for policymakers and administrators preparing for the 2027 Census.

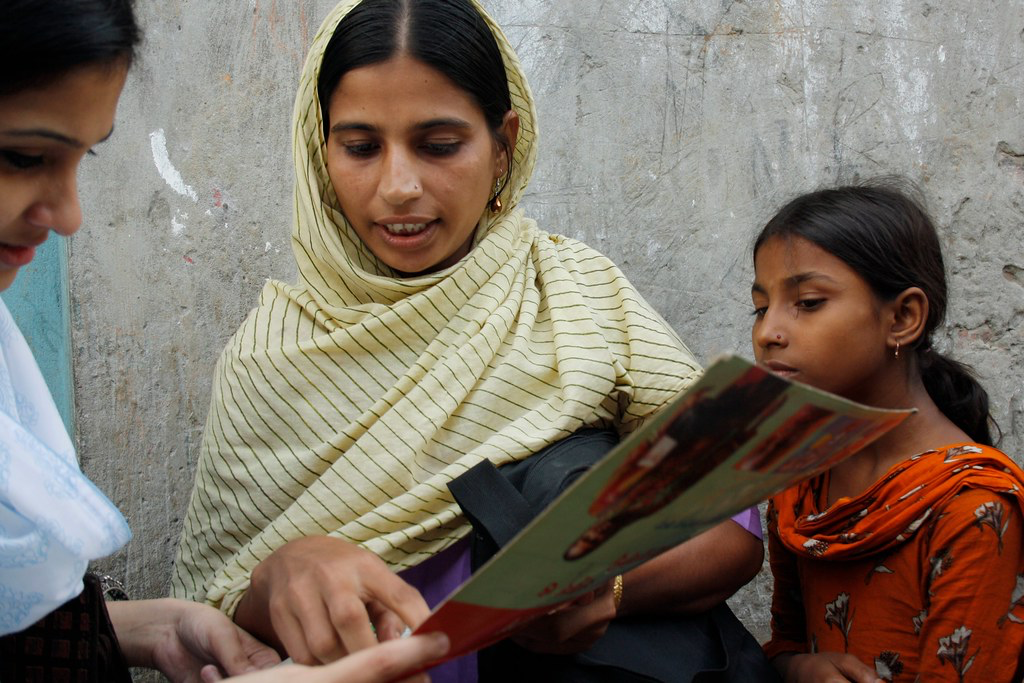

The Union Territory of Jammu & Kashmir undertook a first-of-its-kind Digital Baseline Household Survey, covering over 24 lakh households across the region in just two months- from January to February 2025. Superheaded by the Chief Secretary and anchored by the Department of Labour & Employment, the survey wasn’t a traditional census—it was an agile, UT led survey which while serving as a comprehensive demographic exercise, was specifically designed to identify potential entrepreneurs for the implementation of Mission YUVA (Yuva Udyami Vikas Abhiyan[1] ).

The results were remarkable—the survey successfully identified 5.43 lakh potential entrepreneurs across the Union Territory, creating a robust database for targeted outreach and support. The exercise stands out for its speed, reach, and digital-first approach—offering key operational lessons for the national Census ahead. Our team at GDi Partners was proud to work on the survey’s design and on-ground implementation, alongside technology partner BISAG.

The planning for the baseline survey began with the design of a structured questionnaire, refined through iterative feedback. The data collection application, developed by BISAG, was rigorously tested in field conditions to ensure it was user-friendly and resilient. A cascading training model was adopted: over 400 master trainers were prepared across divisions, who then led hands-on, district-level sessions for enumerators. Crucially, experiential learning was embedded into the rollout—each enumerator operated the app in real-world conditions for a full week before the live survey began. This approach ensured that digital literacy was not a limiting factor on the ground.

The region’s unique geography—with sparsely populated panchayats, mountainous terrain, and fluctuating internet—makes it a natural stress test for any digital effort. And yet, with careful planning, within one month, the entire population was covered digitally, and with integrity.

Technologically, the system was designed to adapt to ground realities. Recognizing poor connectivity, offline data entry was enabled. To ensure data integrity, dropdown menus and auto-validation logic were used to minimize manual errors. Supervisors had access to live dashboards showing daily progress, and geo-referencing allowed field monitoring in real time. Despite initial challenges, including application crashes due to the immense load of simultaneous users, the system was quickly enhanced and optimized. The learning curve was steep but manageable—while the first week saw slower progress, the daily coverage soon reached 80,000 to 90,000 households as enumerators became more proficient with the technology.

For the first time, the administration has a complete, digitally mapped, socio-economic profile of its population—enabling targeted outreach for self-employment schemes, personalized follow-ups through helplines, and data-informed campaign design.

This is precisely the kind of data-intent fusion that India’s 2027 Census must aim for. Instead of viewing the census as a one-time population count, we must see it as a foundation for targeted governance. With digital tools, we can collect additional variables—education level, employment status, skillsets, aspirations—without delaying outputs. Combined with state dashboards, this can help policymakers not just respond to needs, but anticipate them.

Of course, there are valid concerns. Can digital tools ensure inclusion in remote areas? What about data privacy and local language access? These are real issues—but J&K has shown they are solvable. By designing for low connectivity, investing in enumerator training, and keeping human oversight at every stage, the UT delivered both coverage and quality.

As India prepares for the 2027 Census, we at GDi Partners believe there’s no need to start from scratch. The Jammu & Kashmir experience proves that with clear intent, strong inter-departmental coordination, adaptive technology, and investment in field capacity, eveen a high pressure enumeration exercise can deliver on both intent and execution. The national census now has the opportunity to build on this momentum—not only to count India’s population, but to understand it better.

The question is no longer whether India can conduct a digital census. That capability has been demonstrated.The real test ahead is not technological feasibility—it is the willingness to scale what has already worked, while adapting it to India’s diverse realities. The Jammu & Kashmir Baseline Survey is not the final answer, but it is an important beginning. And in a country of our scale, beginnings like these matter. The success of the exercise shows that a digital, decentralized, and purpose-driven model of data collection is not merely aspirational—it is already becoming reality. And as we prepare for Census 2027, this approach may not just be beneficial—it may be essential.