Growing up in a small town near rural Chhattisgarh, I was a curious child who observed difficulties in attaining quality education for all, from indifference to limited access. My mother’s profession as a government school teacher allowed me to visit government schools and observe the poor public education system. These visits sparked my interest in the domain of education and my zeal to closely observe the functioning of the public education system of India.

Working in a state-run classroom

Fast forward ten years, my first engagement with students, as an integral part of the education system, started as a Fellow with Teach for India. I was placed in a Municipal Corporation of Delhi (MCD) school in New Delhi to serve as a full-time teacher to children from low-income communities in an under-resourced school. This engagement posed a series of challenges and subsequently enabled learnings about the state of public school education in the national capital of India.

Partnering with teachers and co-teaching helped me decipher the administrative functioning of school education, the role of teachers as implementers and school principals as management units. My initial notion of government school teachers of India being responsible for poor public education began to change.

Adopting the role of a teacher helped me acknowledge the roadblocks they face in the system. My major criticism of the system became the low participation of beneficiaries (teachers and students) in program designing and policy-making. From being rigorously involved and overworked in administrative work to single-handedly managing the distribution of rations in the community during the covid outbreak, their working hours are spent mostly outside the classrooms. Moreover, a lack of proper incentivisation mechanisms and a dearth of teaching resources limit their motivation, innovation and mobility to work at par with high-performing private school teachers of this country.

As an on-ground agent of change, I had a closer view of the implementation of education programs & policies and the challenges that come with it. This experience further led me to acknowledge the limited participation of teachers in policymaking and program design.

Working in the state department of education

As I transitioned out of the Teach for India Fellowship and subsequently joined GDi, my purview of stakeholders in education increased drastically. Mission Buniyaad, the project I am currently placed in, aims to enable digital learning for 10 lakh girls across the state and improve learning levels by 8% points in Grades 8–12.

During the shift from being an educator in the classroom to being a consultant at the department of education in the state of Rajasthan, what remained constant was the result of both stints, that is, providing access to quality education to improve student learning outcomes. The two professional journeys can never be seen in isolation as one subsequently led to another. The learnings from my work at Teach for India define my approach to making structures, designing programs and optimising departmental capacity in leading those programs.

Solving problems seen as a teacher at TFI

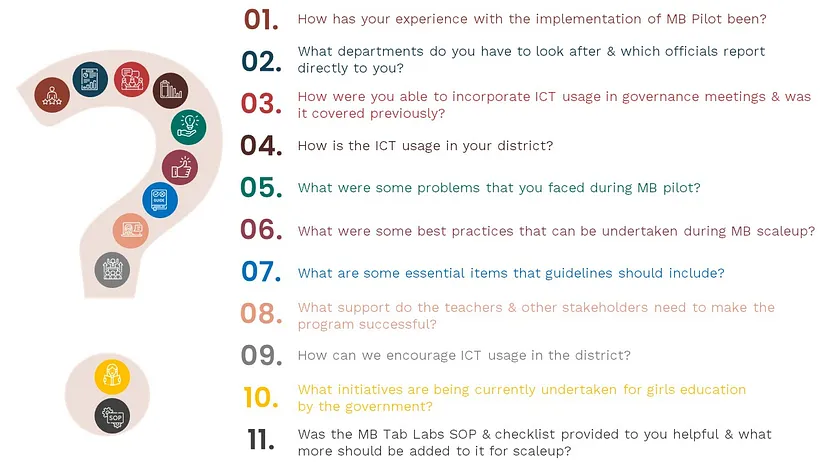

My approach to program designing keeps the participatory practice at the centre to solve low stakeholder participation in decision making. Involving and engaging teachers, ICT in charge, School principals and other partner organisations ensures collective accountability and investment in the program. During the strategising & planning of the program’s scale-up, for example, a series of interviews (image 1), focused group discussions were scheduled to understand the needs of teachers and school stakeholders. This ultimately makes them the decision makers of their work by giving them a space to voice their opinions on challenges they foresee and suggestive measures to avoid them. These diverse voices helped us table new perspectives, ultimately helping form new and contextualised program designs.

Expanding the scope of stakeholder interaction

Regarding my stakeholder engagement, the shift from interactions with school-level stakeholders to interactions with the department, my learning and understanding of centralised (State level) and decentralised (Block and panchayat level) governance mechanisms and the vested powers has increased. Moreover, the interdependencies and cross-vertical collaboration within the education department have opened a new set of learnings concerning state governance and administrative process. For instance, in Mission Buniyaad, there’s a need for a strong working alliance between five cells of the Samagra Shiksha Abhiyan, namely ICT, Teacher training, Gender, Community mobilisation and Quality. The ICT department enables access to digital education in schools, whereas the gender and community engagement cells ensure active participation and awareness of the community towards girls’ education. For an ambitious goal of providing access to digital education to girl students in a state with low digital permeability and literacy, an active process of equipping teachers with digital skills requires the participation of quality and teacher training vertical. When pulled together, this dynamic cohesion between verticals creates a program that impacts millions of student lives.

Concluding Thoughts

Over the last couple of months, wearing the hat of a social impact consultant helped me witness the expanse and depth of work that happens at the state level. It also trained me to find a delicate balance between access and quality, where the quality of any intervention can only be ensured once the program has been made accessible to the beneficiary.

While I’m still working on achieving an optimum level of stakeholder coordination and satisfying the demand and timeline of the program, my current journey has put me on the right path of exploration to create impact. I’ll share more details from this journey in blogs to come!