A year ago, I joined GDi, a start-up in the governance-social impact consulting sector, on the back of a Bachelors and Masters in Economics, and a stint as a policy researcher. I have always been interested in the ‘impact space’. My decision to join GDi was driven by a desire to drive real-world change. In this blog, I want to share my experience of the last year, where I have had a ring-side view of an innovative financing idea taking shape in the government-social impact ecosystem.

Outcomes matter

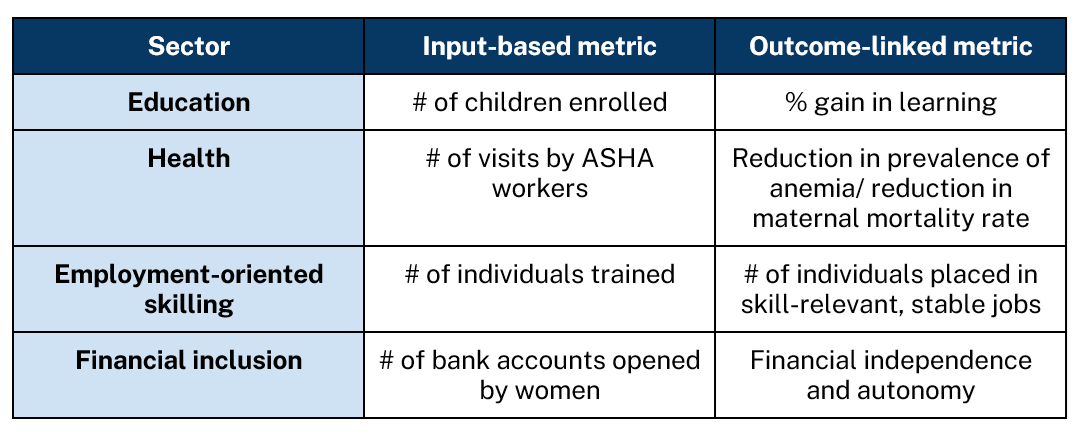

Funding in the development sector comes from sources such as the government, multilateral agencies, philanthropies, and CSR, among others. Funds have traditionally been provided on the basis of inputs and efforts, assuming that it would lead to the desired outcome. For example, in education, funding is tied to delivery of ‘x’ number of teacher trainings, as opposed to improvement of teacher competency or student learning.

Globally, there has been a recognition that inputs do not always mean outcomes. This has led to a shift in conversation towards results. The Framework for Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) drives action through an outcome-oriented target approach. Since 2011, the World Bank has added ‘Program for Results’ (PforR), using results-based financing as a form of aid. Globally, 275 impact bonds (tools for outcome-linked contracting) have been launched, including several in low & middle income countries

Comparing input v/s output-linked model

References

https://www.britishasiantrust.org/media/4019/case-study-report_go-lab-british-asian-trust.pdf https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/futurewewant.html https://www.worldbank.org/en/programs/program-for-results-financing

The challenge with the traditional input-based approach to financing is that it doesn’t account for quality of expenditure – the impact on the end beneficiary.

Considering the example of EdTech, the government provides EdTech in schools, under Samagra Shiksha’s ICT and Digital Initiatives. The ultimate goal of ICT in school is improvement of student learning outcomes. Since 2004, the government has spent Rs 15,000 cr on procurement of ICT infrastructure. While 68,000+ labs have been set up, anecdotal experiences from schools shows sub-par usage of labs (owing to multiple challenges, like maintenance, quality of ICT labs, lack of ICT instructor), and its impact on learning levels is neither known nor measured.

Linking funding to achievement of outcomes

Outcome lens in funding is important because it shifts the focus from expenditure and effort, to the change experienced by the citizen. In a world of limited capacity and unlimited needs, it is imperative that public funds are put to their best possible use. Outcome-based funding aligns incentives towards delivery of outcomes, and the government pays for what it ultimately cares about.

Over the last several months, I have had the opportunity to observe this model in action in the EdTech sector, through NITI Aayog’s pilot outcome-based funding program being implemented in four districts of UP. In this program, the payment to the EdTech Provider is linked to the outcome of improvement in learning levels of students. Linking funds to the end outcome, drives higher order ownership of the Provider to the key inputs along the way such as quality hardware, learning software, lab maintenance and alignment of headmasters and teachers to drive usage.

The NITI program is designed to provide students tablets containing Personalized Adaptive Learning (PAL) software aligned to their curriculum, and field staff to support teachers in implementing the in-school program. It is a 2-year program covering students of Grades 3-8 in 280 schools, for Hindi, Maths and Science.

The usage of EdTech in the program began in July 2023, and since then we have seen 20 lakh hours of usage by 74,000+ students, amounting to an average per student usage of 23 hours! While the question of outcome achievement will be settled by a third party outcome evaluator, usage and learning metrics across the 4 districts suggests a positive correlation.

This has been possible due to a remarkable amount of energy and ownership for the project in the schools, and a higher degree of involvement and accountability by the Service Provider. The Provider has –

- ● Worked closely with headmasters and teachers at the school-level to drive usage and learning.

- ● Provided regular updates to the DM and education department officials at the district level for data-backed monthly review.

- ● Trained and re-trained over 500 teachers, and followed up with capacity building of teachers through field staff.

This is in spite of operational challenges of limited electricity in schools, shortage of teaching staff, and some pockets of resistance to a new program. However, as the stakeholders have become familiar with the program, reviews have regularized, and field staff have demonstrated value, the usage has increased.

What’s different about pulling off an outcome-linked program?

Quality-focus

Due to linkage of payment to learning improvement, emphasis was placed on ensuring procurement of a quality EdTech product. While usually the government selects the lowest cost or L1 bidder, in procuring for an outcome-linked funding model, 80% weightage was given to technical (quality) parameters and 20% to financial. Bidders held a demonstration of their product and even provided a sample to the district administration.

Set-up costs

Given the importance of learning outcomes, an in-depth study was conducted to define the outcome metric, set a target and define the methodology for evaluation. Further, a third-party outcome evaluator was selected to measure and certify gain in student learning outcome. All of these details were clearly defined in the RfP to provide as much clarity upfront as possible, and ease the path for outcome-linked payment later.

Capacity building

Given the novelty of the idea, and lack of prior experience in a quality-led tender there was an initial resistance from district stakeholders for implementing the program. We solved for these by holding meetings with a vast breadth of stakeholders to seed the idea of outcome-linked funding. Further, we worked closely with government stakeholders and external partners to conduct training in technical bid evaluations.

A journey covered, but more road awaits

While the design and implementation of this program can serve as an exemplar, some questions remain. Firstly, the current model places the full risk of outcome achievement on the service provider. However, a risk investor would be better equipped to handle risk. Hence, the next step is incorporation of a risk investor into the government contract.

Partly as a result of the risk allocation, this program had limited service providers who participated as bidders. Through better communication, capacity building and redistribution of the risk, the ecosystem of service providers needs to be built to ensure success of outcome-based financing.

Lastly, while in this program a philanthropic partner has on-boarded the outcome evaluator, in a potential scale-up this cost must be borne by the government or outcome funder. This can be through an independent evaluation cell in the government, or through clever identification of outcome metric which is captured external to the contracting party.