Growing up in one of India’s smaller towns, I was often awestruck when I spotted vehicles that said ‘On Government Duty’’ in bright bold red. As a child who was fascinated with this, I assumed that it was something unique to my hometown. However, when I moved to Delhi and spotted many such vehicles around the India Gate, I often wondered about the similarity in the nomenclature of all these vehicles.

A few years down the line, I joined the Chief Minister’s Good Governance Associates (CMGGA) programme in Haryana. As a CMGGA, I had the opportunity to work at the district level. It was here that it dawned upon me that the word ‘Government’ is quite nuanced and tends to be used interchangeably among various levels of the government (geographically — centre, states, districts and even villages, functionally — executive and legislature). The same word can also mean different things to different people — for some people, the Prime Minister is the government whereas for some others the local transport office that issues driving licences is the government. However, for people within the government, there is much less confusion — officials in my allotted district tended to use the aura of “Government of Haryana” as their introduction rather than ‘transport officer’.

But why is this relevant to this blog? Or to social impact consulting, in general? As social impact consultants, we at GDi, believe that government is one of the biggest levers to creating large-scale and long-lasting impact. Hence, many programmes that we undertake end up involving governments in some ways or others — either directly as clients or as important enablers or regulators in making policies. Hence, while diagnosing any problem statement or designing any large scale transformation programme, it is imperative for us to always break down the term ‘Government’ to a specific level and department/officer for better problem solving and structuring.

Post the opportunity to work closely with a district administration (during the CMGGA programme), I have supported the State Government of Rajasthan in designing a state-wide digital education project ‘Mission Buniyaad’, and worked on ‘Modernising Agriculture and Allied Sectors’ with State Government of Odisha for better market linkages for millions of farmers. These experiences have given me a new lens through which to look at the Indian governance system.

In this blog, I will highlight some of my observations regarding the different roles played by the different tiers — with a focus on State government and District Administration — in various programmes and the challenges I see in their synchronisation.

1. Scope of work

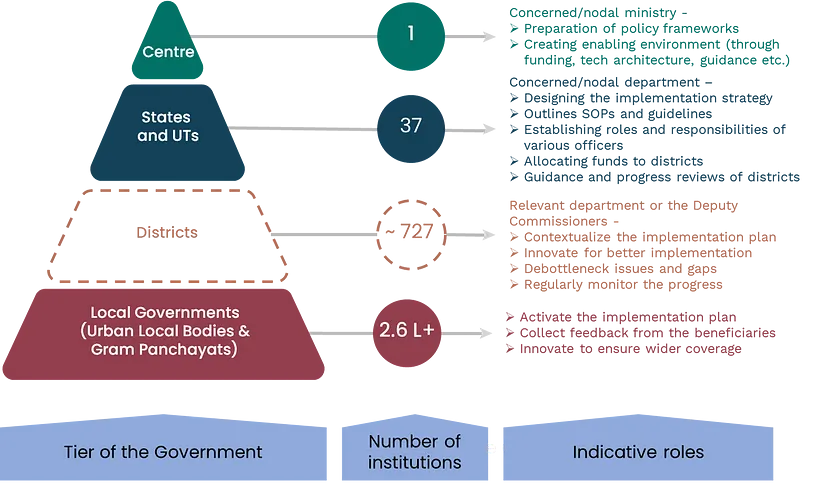

India follows a three-tier governance system: 1) Centre Government, 2) State Governments, 3) Local Governments — Urban Local Bodies (ULBs) or Gram Panchayats (GPs). District Administration plays an important role in bringing together these 3 tiers of government.

When I was working as a CMGGA at the district level, my role was to support the Deputy Commissioner (DC) in ensuring the smooth implementation of the State Government’s flagship programmes. Officers at the state headquarters would design programmes/schemes/projects, and we would receive pre-designed strategies, Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs), Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) etc. . We would ensure implementation by customising the strategies and SOPs as per local context, monitoring the progress, and providing regular updates as well as any feedback to the state team.

However, in Mission Buniyaad, as the state level Programme Management Unit (PMU), we are in charge of designing the strategies, creating SOPs, and defining KPIs which will be leveraged by the district teams for implementation.

Adding the scope of work of the Central Government and the Local Governments, the responsibilities of different tiers of governments, at a broad level, can be understood through the following infographic:

2. Availability of human resources

During my time at the district level, I noticed that one of the major bottlenecks in the ground machinery is the employment of low-skilled employees in various government offices. The low level of skillset — many a time — reaches an extent where IAS officers have to correct simple grammar and spelling mistakes in letters or office orders. I realised that this is because of 2 reasons -

- districts have a high level of vacancies for permanent positions but most of the time can not hire directly because the power to hire permanent employees lies with the state (through Staff Selection Commissions)

- districts have the power to hire for contractual positions but are not able to hire sufficiently skilled employees. While there are multiple reasons behind this phenomenon (political references, lack of supply in the district etc), the dearth of funds allowed for this hiring is the prime reason. To take an example, a full-time computer operator (contractual position) can only be hired at INR 8,000 per month (without any provision of overtime pay, appraisal or promotion) which doesn’t incentivise the highly skilled applicants to apply for these positions

All funds to districts flow from the state level (whether it is the Union budget or the state budget) and hence it is the state’s discretion to re-allocate the budget amongst various expenditure heads and tiers (state/districts) based on the need. Some discretionary funds do exist at the district level (like district development fund, MP-LADS, MLA-LADS etc), however, the majority of funds received are earmarked for specific activities and there is lesser flexibility to re-allocate them without the state’s prior permission. This also affects the human resources that districts are able to employ.

The availability of resources at the state level is typically better because they can either deploy someone from the district offices to take charge of state-level positions or can engage with external consultants (through direct hiring or support from philanthropists, foundations etc) since they are able to provide the requisite compensation/scale of operations. This is also the primary reason why one can see a significantly larger number of supporting private agencies (like consultants, NGOs, multi-laterals etc.) at state offices compared to any district level office.

3. Level of agility in programme customization

Any large-scale project impacts thousands, if not lakhs, of lives. Hence one would assume that strong feedback mechanisms are bound to exist for such projects. However, government machinery faces multiple issues in ensuring — (i) a strong feedback loop and (ii) a short turn-around time of grievance redressal.

At the forefront is the issue of perception. State or centre level officers do not have direct visibility of the performance of the project on the ground and have to rely on the reports coming in from the districts. But due to the fear of being perceived as incapable or non-compliant, field-level employees or officers feel apprehensive about sharing the accurate status with their seniors, thereby leading to inaccurate data reporting and a lack of any feedback for project improvement. This data discrepancy can be easily seen in Swachh Survekshan scores released by the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs every year. While working with the Government, we observed that while most of the Urban Local Bodies (ULBs) would score full marks on Door-to-door garbage collection coverage parameters, in reality, they would hardly have enough vehicles to cover all the wards.

The second challenge with the feedback loop is that of the turn-around time of the raised issue. At the state level, the resolution of grievances becomes complicated due to the involvement of a larger set of stakeholders — any change in the strategy will affect all the districts and hence has to be decided after thorough discussion. While WhatsApp groups have expedited the communication of issues and resolution between state and field, the process of reaching the resolution still remains a barrier to ensuring a quick turnaround time.

At the district level, the intensity of both the issues is significantly lesser due to the fact that both the quantum of information handled and the number of stakeholders involved are lesser. This allows any department head to verify the information provided by the field officers and to be agile and find innovative ways to combat issues during the implementation phase of any project.

4. Existence of cross-department synergies

India follows a functional setup of ministries and departments. Each state government has multiple departments — the Department of Education runs all government schools and regulates private schools, the Department of Agriculture works for farmers’ welfare, etc. These departments can’t function in silos and have to depend on each other to offer comprehensive services or schemes to the citizens. Let’s see using an example — ‘Department of Health and Family Welfare’ (DoH&FW) leverages the network of schools (handled by the Education department) to increase the reach of immunization programmes; similarly, civil and construction works for all the departments are usually overlooked by the ‘Public Works Department’ (PWD) etc.

At the district level, each department has its own field office and staff who coordinates and leads the department activities on the ground. But all of the field offices have an additional line of reporting to the office of Deputy Commissioners (DCs, also known as Collectors or District Magistrates).

One of the primary roles of a DC is to coordinate activities of various departments to ensure smooth implementation of the projects on the ground. As a result, they are also a part of almost every district level committee/board/society that involves multiple departments. DCs help in ensuring synergies between departments and quick resolution of conflict, if any. While the responsibilities of all departments in the district translate to a lot of workload for the DCs, they also enjoy the privilege to have a strong say in all the matters pertaining to their district. During CMGGA, we regularly leveraged this positioning of DCs to review the progress of the projects and to debottleneck the cross-department coordination issues.

At the state level, the complexity of inter-departmental coordination increases as each department is headed by a Minister along with a senior bureaucrat (typically an IAS officer) acting as Additional Chief Secretary (ACS) or Principal Secretary (PS) of that department. All of these ministers or bureaucrats have different priorities for their departments and are usually fully occupied with multiple things. Hence, whenever a project requires multiple of these senior officers to come together and make decisions, it often becomes difficult to align all of them on the same actions. This raises the need to involve the Chief Secretary of the state or the Chief Minister to drive results in the most important meetings. During Mission Buniyaad as well, we were exploring the possibility of connecting all schools to the BharatNET network operated and maintained by the Department of IT. But due to a lack of coordination between the Department of School Education and the Department of IT, it didn’t follow through.

Conclusion

I have enjoyed working at both the district and state levels. Working in the district has helped me in developing a realistic and bottom-up view of how governments function, key challenges faced and how large-scale programmes are actually implemented on the ground. These learnings now form the bedrock of my work at the state level, where I am learning to take a balcony view and think from a systems lens to design ambitious programmes aiming to transform the lives of individuals and communities.

As social impact consultants, it is imperative for us to understand the functioning of (and engage with) all levels of government so that we can stand in their shoes and understand the ecosystem they are working in. This understanding would also help us in developing a user-centric approach to problem-solving, keeping in mind the broader interests of the target beneficiaries and creating maximum impact.